Where does old VR go to die?

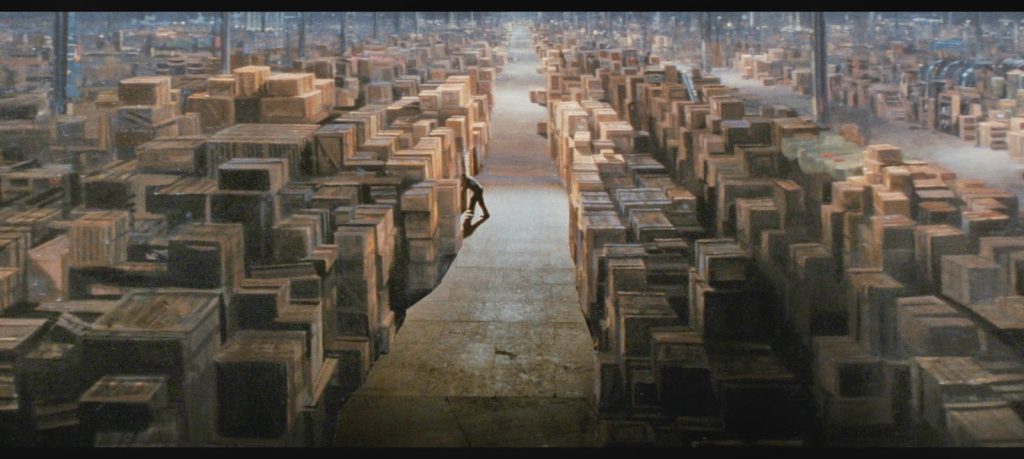

If you’ve ever noticed public VR exhibits (museums, special venues), you may have wondered for a moment if you could just enjoy the experience at home. After all, they’re often using the same headsets and usually don’t rely on any special other equipment. While some of these can be downloaded for personal use, this isn’t the norm. Unlike a movie eventually being released on disc and streaming, custom VR experiences are often just forgotten. All of that creative and technical effort is just wasted. Some team spent lots of time (and someone’s money) to create something special and now it might as well be shelved in the warehouse at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Except, even that’s not necessarily a good description. Those files are probably sitting on someone’s hard drive. The person in charge of it has probably long since moved on to other projects. With no long-term planning, it’s just waiting to be forgotten. Like with many digital assets, we don’t really have a great way to preserve apps like we do with books and music (Library of Congress), and movies. There are a few reasons for this.

Archival formats

One problem is the myriad of formats (physical and digital). Think about personal music collections. Vinyl records? Cassettes? Compact discs? MP3 files? Movies are similar. Whether it’s film, laserdisc, VHS, DVD, or Blu-ray, you either need the right physical player, or you need a way to transfer (rip) them to a hard drive as a playable file. What kind of file though?

If you chose to rip all of your CD’s to MP3 a few years ago, you almost certainly lost some quality since it’s an imperfect process. A few years later, there are newer formats and quality choices. You can keep ripping that music to newer formats or quality levels periodically, but only assuming you kept the original media. If not, it’s like photocopying a photocopy. Even the best machine can’t make a third-generation copy better. (Note that exact digital copies don’t lose quality, it’s the process of encoding them in different formats where that can happen.) If you don’t keep updating them, at some point you won’t be able to play them. Even if you can keep upgrading to newer digital formats, though, nothing is forever.

Nothing lasts forever

Think about old PC games from a decade or so ago mostly sold on CD. You might have some of those old discs. They get scratched with time though. Worse still, your modern Windows 11 laptop can’t play the game properly, assuming it even has an optical disc drive! Needing an old PC for that classic game CD is like needing a record player for your old albums. It becomes a pain pretty quickly.

All this to say, digital preservation is great, but many VR experiences might as well be old demos of garage bands on cassette, long forgotten in a shoebox. Who knows how many hours of potentially good music is out there forgotten? If we want to preserve these exhibited VR apps, there are two things we need to do: make the apps available, and find a way to ensure that they are playable.

Two simple requirements

Making them available is the easy part. If these were made available on Steam and other storefronts, they would be indexed and searchable and people could enjoy them on their own. Once an exhibition reached its end, a few months to a year later the VR component could be released to the public. Just like movies, you could get the original experience, or wait to try it at home. Whether this is for large commercial projects like Dinos Alive or something smaller like The Seattle Fire at the Seattle Public Library, if it was worth making, it’s worth keeping it available!

The second issue is, sadly, much more difficult to solve. Like with the old PC game CD’s, generally once something is released, it doesn’t get updated as PC’s and headsets evolve. For example, if you had bought a VR game for the older Oculus Quest Go, you’d be very disappointed to learn that it doesn’t run on any other headset just a few years later. Since the Go is no longer for sale, these titles are basically abandoned. In a few cases, the developer will rewrite/update the app for newer headsets, but it’s usually not considered to be worth it.

Emulation is the best form of flattery

The Internet Archive has come up with a novel solution to archive old PC games (in addition to so much other media they archive). They store the original files on their servers and let you play them in a web browser through a technology called emulation. They actually simulate an older PC right within your browser so the game can party like it’s 1999. Emulation is also used so people can play old arcade games or console games for which the required hardware is no longer available. Think of emulation as translation. The game/app only knows how to talk to older hardware. Emulation translates its “dialect” so modern hardware understands it.

In the VR realm, emulation could also be extremely beneficial. The dominant current ecosystem is called OpenVR. This is an open standard that defines how VR apps should be written to run on almost any headset (although apps can still require certain headsets for various reasons). SteamVR conforms to OpenVR and is more visible which is why most headsets these days support SteamVR. Even the proprietary Quest 2 uses OpenVR, although it lacks the processing power to run full PC VR titles, so you need to get your apps from their dedicated store (unless you use AirLink to stream them from a PC). Ideally, anything written for OpenVR will work on future headsets, although this isn’t a given. With emulation, apps written for older headsets could be given an extended lease on life with newer headsets.

Publish or perish

Before any of this matters though, VR titles need to be available to everyone. I’m not implying they need to be free, just available on public storefronts. I suspect that smaller institutions like libraries and private museums just don’t realize that anyone would be interested in their narrowly-scoped exhibit-specific efforts, or perhaps assume releasing an app on Steam or the Oculus Store would be too difficult or costly. With other things to do, people move on to other projects and their great work languishes.

This is a real shame because I’m confident that there are hundreds of such works out there that have been shelved. I’m sure that the developers and creative folks would love to see more people get to enjoy their efforts. It doesn’t require much work to publish, and I think many organizations would be surprised at the interest there would be in their works.

Are you part of a team managing exhibited VR experiences for an institution or other organization? I’d love to help you get started on getting your works out there. Look for my upcoming post on this for more details!

Leave a Reply